The Scarce Resource in Course Prep→Time

Why Principles teaching begins with trade-offs long before class starts.

During this summer’s course prep, I kept coming back to one scarce resource: time. Three experiences nudged me toward better ways to spend it:

Econiful’s Workshop: the syllabus as invitation

Cohen’s history of literacy-targeted economics: where have we been?

A literacy-targeted course: is there a good example?

1. A syllabus for students

At Econiful’s Ahead of the Curve professional development workshop, I learned to make my syllabus headings more student-centered.

Old vs. new headings:

Learning Goals → What will you be able to do by the end of this course?

Course Description → Why should you be excited about this course?

Course Schedule → How will your learning be organized?

Takeaway: A syllabus should invite students into your classroom.

2. What is the history of literacy-targeted principles?

Cohen’s (2023) history of the literacy-targeted movement was eye-opening. It showed me that educators have wrestled with this issue for decades. Reading that history prompted me to rethink my own course goals.

I used his suggestion again to refine my goals using backward design: start with the goal, then plan steps backward. Each emphasizes a skill students can practice instead of memorized topics:

Ask useful economic questions and gather reliable evidence to answer them.

Reason about choices using economic and ethical frameworks to explain trade-offs and outcomes.

Work with data to spot patterns and connect them to the real world.

Apply economics daily by bringing economic reasoning into personal decisions and test what we think we know.

Communicate clearly so others can follow the reasoning and join the conversation.

As Cohen (2023) argues:

“When learning outcomes shift focus from content—what students should know—to competencies—what students should be able to do with the content—course design changes profoundly.” (129)

In short, show students what they can do and why it matters.

3. A Starting Point for Literacy-Targeted Course Design

Michael Salemi’s literacy-targeted Principles course remains one of the clearest examples I found for a course that covers both micro and macro. On a personal note, Salemi taught me as an undergrad at UNC in the early 1990s. I still remember his classroom vividly, so it feels fitting to return to his work as I rethink my own teaching.

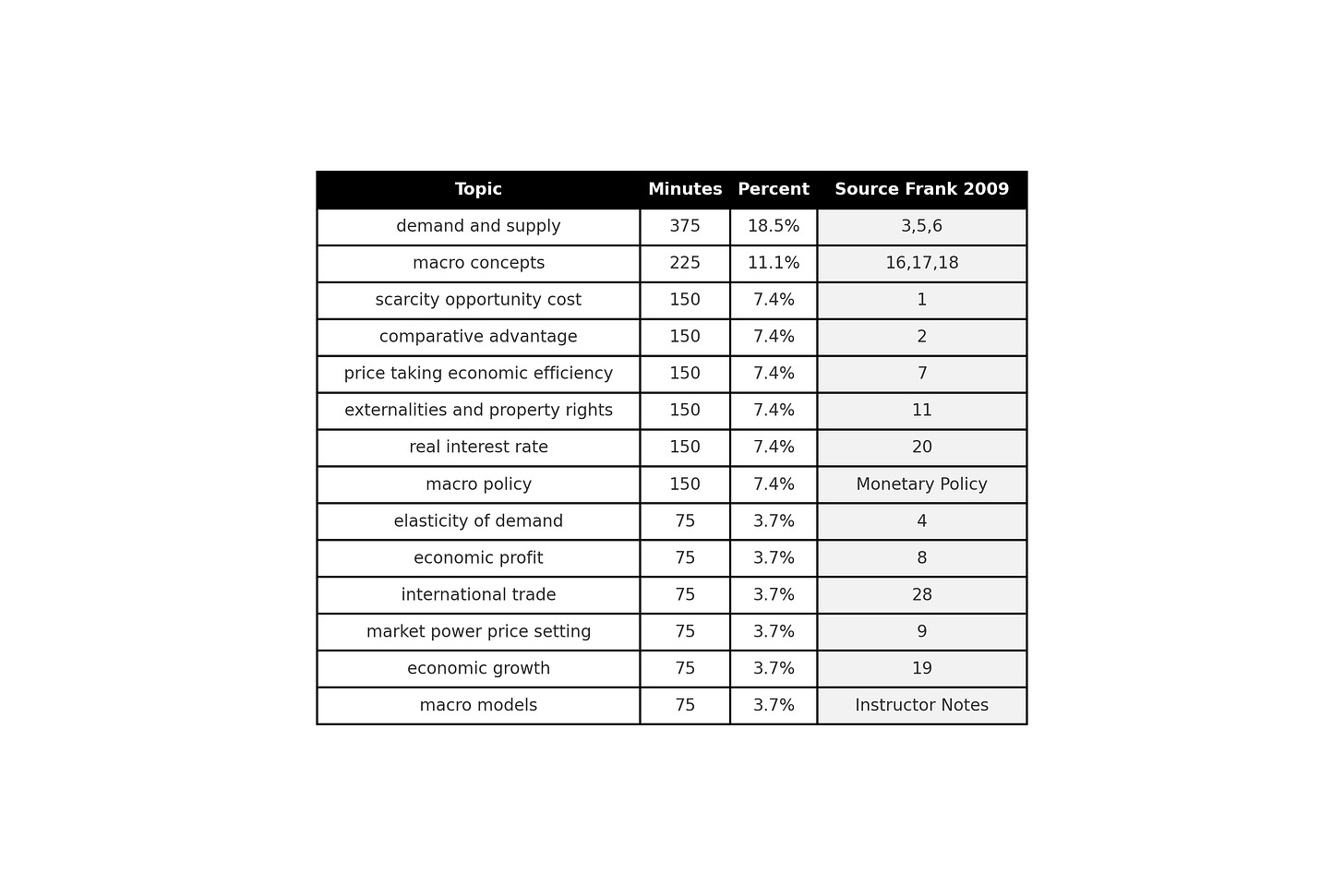

My notes about Gilleskie and Salemi’s (2012) “Short List” in a literacy-targeted course, ranked by class time. See their Appendix A for detail and discussion.

Two lines from Gilleskie and Salemi stayed with me:

“In a literacy-targeted course, students study a ‘short list’ of concepts that they can use for the rest of their lives.” (112)

“There are three ways in which the LT course targeted economic literacy. First, the LT course covered fewer topics than do traditional principles courses. Second, the course reallocated the resources recovered by omitting some traditional topics to teaching fundamental economic concepts more intensively. Third, the course included assignments that helped students gain a deeper understanding and working knowledge of fundamental concepts and helped them transfer their understanding to contexts and tasks they will encounter throughout their lives.” (113)

The short list will always be debated, and that is healthy.

Wrapping up

Now comes the hard part: choosing the short list that helps students carry these five goals beyond the course.

If you teach Principles, I’d love to know which short list has stuck with your students.

References

Cohen, A. J. (2023). What do we want students to (know and) be able to do: Learning outcomes, competencies, and content in literacy-targeted principles courses. The Journal of Economic Education, 55(2), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2023.2282016

Gilleskie, D. B., & Salemi, M. K. (2012). The cost of economic literacy: How well does a literacy-targeted principles of economics course prepare students for intermediate theory courses? The Journal of Economic Education, 43(2), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2012.659639